I’ve been captivated by del.icio.us from the moment I found the site

in early 2004. I don’t remember how I found it, but it captivated me

immediately. It was so minimal it wasn’t even clear what the site was

for, but as soon as I figured it out, I was hooked. I think

del.icio.us was (and remains) far more important and innovative than

is generally recognized.

The Social Site for Solipsists

An aspect of del.icio.us that is rarely discussed is that while it is

the grandfather of all social sites, unlike most others, del.icio.us

is ridiculously useful even if you are its only user. When I save a

bookmark on del.icio.us, and tag it, I do so entirely selfishly. I

get two intense benefits from storing bookmarks on del.icio.us, even

if no one else uses it. The first is that I can access my bookmarks

equally easily from different browsers and different machines. The

second is that I can organize them using tags, which are dramatically

more useful than folders.

(Search isn’t as good.)

(Many people claim that the advent of full text search has eliminated

the need for organization. I disagree. While there is no question

that Spotlight, on the Mac, full-text search in gmail, and equivalent

solutions elsewhere, have been enormously positive, I find that I

still struggle to find email, particularly, because I tend to get

thousands of results when I search. The brilliance of tags is that

not only can I identify bookmarks (or emails) of interest by using a

tag; I also exclude all the items to which I didn’t attach that tag.

This turns out to be almost more important.)

The Social Solipsist

The cross-browser/cross-machine accessibility of bookmarks and the

organizational power of the tag are the two most important benefits

that del.icio.us brings for me, but that is not to suggest that the

social aspect is unimportant. It is also remarkable.

With del.icio.us, of course, bookmarks are public by default. (In

fact, I’m pretty sure there were no private bookmarks initially.)

Anyone can go to del.icio.us/njr and see

all but a handful of my bookmarks. And anyone interested to see the

bookmarks I have tagged with Fluidinfo, need only visit

del.icio.us/njr/fluidinfo

to see them. (Notice the zen-like, RESTful, perfect URLs.)

But there’s more. To see what anyone has tagged with fluidinfo, I can go to del.icio.us/tag/fluidinfo. And here something truly remarkable happens.

Despite the complete lack of any organizing principle or oversight,

there is rich structure in the tags. The tagsonomy, or folksonomy, as

it is called, simply emerges, and is useful. When Google fails me, I

often go to del.icio.us, and look up what I want using a few tags.

The results are often better than Google’s, because everything in

del.icio.us tagged with a given word has been chosen by someone, in

vast majority cases, for his or her own selfish (or at less,

non-altruistic) reasons. There is no voting on del.icio.us. It is

not like reddit, or digg; there is only saving and tagging. And

though you might think that this would lead to chaos, it doesn’t. It

is true both that words are ambiguous, and that there are many words

with similar meanings. But this hardly seems to matter. If you look

at a tag with multiple meanings, you may find bookmarks for sites

covering each meaning, but that isn’t a big problem, and you can

search on tag intersections anyway. It’s also true that the first

tag you search on might not be the one most people use. That also

turns out to be a largely unproblematical. The tagsonomy that

emerges from millions of selfish actions is surprisingly

clean, regular, and useful. It is almost mirac.ulo.us.

for:alex with love

Before the site even supported for: tags, I started tagging sites that

I thought would be of interest to my son, Alex, with an alex tag.

(Did this mess up the tagsonomy? Not obviously.) And he would periodically

go to del.icio.us/njr/alex and find

the sites I’d saved for him. I save origami sites for my mother, who

folds, at del.icio.us/njr/origami. It

works.

But del.icio.us then made this even better by introducing for:

tags. I can now actually send bookmarks to Alex with a simply by

using a for:alexradcliffe tag. When he goes to the site, he sees

them. It’s mar.vello.us.

Love at First Site

Since adopting del.icio.us, I have used it more-or-less daily and have

found it so spectacularly useful that I have built a number of aspects

of my digital life around it. One of these is that I have a dense

home page, for all of my browsers, that is built by extracting

everything I’ve tagged with home and structuring them into a dense

page that has all my most important sites. I have over a hundred

links on this single dense page, and it serves most of my common

internet needs, both on computers and (reformatted) on my phone.

(Read this

to see it, and get the code by following the instructions here

, if you’d like your own).

Christmas Carol

Joshua Schachter, the banker-turned-internet-entrepreneur who built

del.icio.us to solve his own need to organize and share bookmarks,

sold delicious to Yahoo a few years ago. He stayed a while but quit

when it was clear that Yahoo didn’t get delicious. It was

apparently Joshua we have to thank for the tags in flickr as well, for

(as I understand it) he spoke to Caterina and suggested that flickr

needed tags. Flickr, of course, is also owned by Yahoo, and, from my

perspective is the only other part of Yahoo that deserves any kind of

future. But John Gruber at Daring Fireball reports that Carol Bartz, who unfortunately

doesn’t get the internet, fired the entire del.icio.us team a couple

of days ago as part of her plan to dump del.icio.us. (I think almost

every change that team has made to del.icio.us since Joshua left has

been retrograde; but I’m still not celebrating.) Charles Arthur, who

does get the internet, nailed the Yahoo fiasco in the Guardian’s

Technology Blog

yesterday:

The trouble with all this? It’s on the internet, so Carol Bartz

isn’t going to see it. If only there were some way to make it

physical so she could read it . . .

Maybe she’ll dump flickr next; Charles Arthur reports that she doesn’t

even have a flickr account.

Enter Terry Jones (@terrycojones; not the Python)

For much of the eighties and nineties I did research in the somewhat

obscure and (then) emerging field of genetic algorithms. At

conferences, I tended to spend time with Terry Jones, who worked

directly with John Holland, the MacArthur genius who founded the

field. Terry and I both went onto other things and we lost touch.

But he was interesting, and I looked him up on the internet one day.

He had a very eclectic home page that, among other things, included a

set of papers he had written about computer storage mechanisms. He

tried and failed numerous times to get these published. I read them

and was captivated by the brilliance and beauty of the ideas in them.

In the papers, Terry discussed search and an embryonic form of tagging

as the two core organizing principles that he thought should the basis

for computation storage and retrieval. This was before del.icio.us, and

before search assumed the prominence that it now enjoys. Terry’s tags

(which he then called attributes) were more complex than del.icio.us

tags, in that they carried values. So while in most tagging systems

you can attach tags as labels to objects, in Terry’s mind you should

be able to attach any information to anything using a tag. So at the

simplest level, you could attaching a rating to something (I rate

Fugitive Pieces, by Anne Michaels, 10). Or you could go further and

attach an image or a webpage or anything at all, to anything else. It

was extremely innovative, and the fact that he couldn’t get them

published says a lot more about peer review than it does about the papers.

(The papers are available

here,

here

and here;

the last was eventually published .)

Terry tried twice to build versions of his idea, but struggled and

basically failed. I got in touch with him after reading his papers,

and enthused, and I think he said I was essentially the first person

who had ever liked his work in this area. He sounded quite depressed.

A bit later, another friend of his, Russell Manley (@rustlem) told him about

del.icio.us, and this was the spur that made him try a third time to

build his vision. This time, he sold his flat, created a company

(Fluidinfo, in which I have invested and to which I

am an advisor) and went for it. The result is Fluidinfo Inc, and its main

product, FluidDB.

FluidDB

I think of FluidDB as like del.icio.us on steroids (though Terry

doesn’t like that description of it). Seen through my

permanent lens of del.icio.us, you can get to FluidDB through a series

of generalizations of a social bookmarking site.

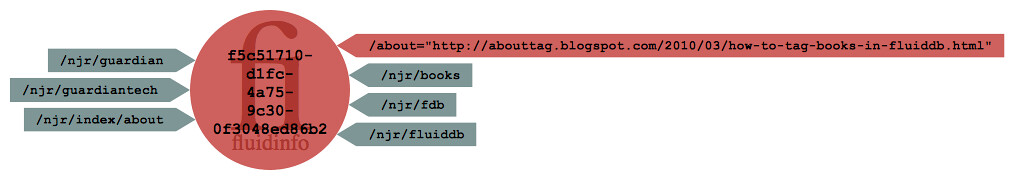

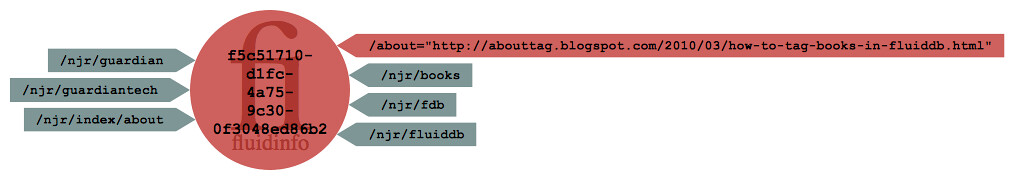

First, instead of just URLs, in FluidDB you can tag anything. FluidDB

contains objects, and the objects can represent anything at all. They

are identified by a special tag (the about tag, fluiddb/about) that

can be used to identify the object. So I have bookmarks for websites

in FluidDB, which are stored on objects whose about is the URL to

which they refer. For example, I have a bookmark for entry in this

blog describing how to tag books from the Guardian’s 1000 books

everyone must read in FluidDB. In a modern, standards-compliant

browser (essentially anything except Internet Explorer), you can see

an image (generated live from FluidDB) showing my tags on that object

by clicking this link.

(FluidDB is completely compatible with Internet Explorer, but my

graphical image generator for FluidDB is not.)

Here’s a static snapshot of the same thing.

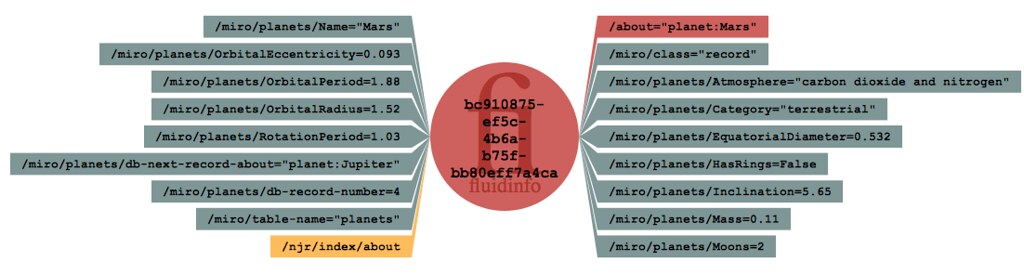

The next thing you add when transforming a social bookmarking site

into FluidDB the ability (but no requirement) for tags to have values.

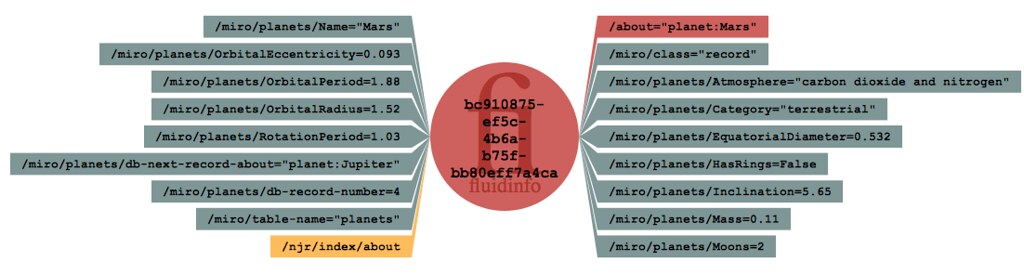

For example, this image shows the

FluidDB object corresponding to Mars, and an application called Miró

has added a bunch of tags to it, with information about Mars. (If you

had a FluidDB account, which you could, you could add your own

information about Mars to the same object.) Again, here’s a static

snapshot of the object.

The third thing you have to add to get FluidDB is a fine-grained permissions system. In del.icio.us, almost everything is shared, though there is the ability to mark a bookmark as private (which means that only you can see it.)

In FluidDB, every tag has its own permissions, with separate controls

for reading and writing and an access-control list. For each of

your tags, you can choose who can read them and who can write them,

either including or excluding people, or making them completely

private or completely public. It’s very powerful

(see Permissions Worth Getting Excited About) and The Permissions Sketch

for more details.)

The fourth thing you add to produce FluidDB is a simple but rich query language. For example, you can find all the planets heavier than Earth with the FluidDB query

There are lots of tools around that let you issue queries against FluidDB (though it doesn’t really have its own interface yet). I have a command line tool that talks to fluidDB, and the command

fdb show -q 'miro/planets/Mass > 1.0' /miro/planets/Name

results in this output.

4 objects matched

Object e06bea33-a000-4294-a7b2-d3245f1481ca:

/miro/planets/Name = "Saturn"

Object e9b022e6-c770-44ad-abaa-1a2cde9a3224:

/miro/planets/Name = "Uranus"

Object 2994f561-8efe-4e13-9374-bf3f9436eac6:

/miro/planets/Name = "Jupiter"

Object 72144788-a59e-4819-a9c9-6b8577e2695b:

/miro/planets/Name = "Neptune"

You can see them in a modern browser by following the hyperlinks on

the miro/planets/db-next-record-about tag on the live version of the

image. You can also use a more point-and-click tool like @paparent’s

FluidDB Explorer by visiting http://explorer.fluidinfo.com/fluiddb/

and typing miro/planets/Mass > 1.0 into the query box at the

top right. (Don’t omit the .0; FluidDB is distressingly

strict at the moment, though I am promised it will change.)

In a bookmarking context, this allows you to do queries like Show me

all the pages that Terry and Russell have tagged with the tag fluiddb

that I haven’t. This is considerably more flexible than del.icio.us

or other bookmarking tools.

The last major thing you add to a social bookmarking site to get

FluidDB is an API to allow applications to talk to it. Of course,

del.icio.us has a (rather good) simple API, but you can’t do very much

with it because part of del.icio.us’s excellence is that it can’t

actually do very much. By definition, anything that you can do in FluidDB

you can do through the API because the API is the only supported way to

access FluidDB at all (though, as I say, there are lots of libraries

and applications built on FluidDB that use the API).

Technically, the API is a RESTful, pure HTTP API that uses

JSON when necessary for exchanging data.

It is documented here.

FluidDB as a new, more powerful alternative to del.icio.us

FluidDB has the potential to be a very interesting alternative to

deli.cio.us. Or perhaps a more accurate statement would be, FluidDB

should be considered as a very serious and flexible place to rehouse

data currently in del.icio.us. The power and flexibility of its

information architecture can allow users to store more kinds of

information, about more things, and to query and recombine that

information in more flexible ways. (In fact, Joshua Schachter is an

investor in Fluidinfo, though I don’t know whether he would endorse

anything I’m saying here.)

Today, however, there are some important limitations worth noting.

The main limitation is that there

is no application like del.icio.us for FluidDB. There are (at least)

two ways to import data from del.icio.us to FluidDB, preserving

everything in the export, but until some work is done building a

del.icio.us-like client application, it will be awkward to use the data

and to add new bookmarks.

I’m confident that over the coming weeks and months, applications will

be built that will provide basic social bookmarking using FluidDB, but

until that time, FluidDB is only really a suitable alternative for

technical users.

There are two other minor limitations today. The first that although

FluidDB has a much more powerful permissions system than del.icio.us,

its design (for rather fundamental and deliberate reasons) does not

make it very easy to support private bookmarks in the ‘natural’ way.

To be clear, it is entirely possible to have completely private

bookmarks in FluidDB: but you need to organize your data in a slightly

more complex structure to achieve this and native FluidDB queries on

private data will have to look slightly different from native queries

on public bookmarks.

Such complexity can easily be hidden from the user by an application,

and again, I suspect that applications that do this will appear. But

they don’t exist yet.

If you do want to import information from del.icio.us to FluidDB,

there (are least) two published ways to do so.

Some months ago, I published some python code to github that takes a

very direct approach, creating a FluidDB tag for each of

your del.icio.us tags and attaching them to objects whose

fluiddb/about tag is the URL for the bookmark.

At the moment, that script doesn’t

upload any information about private bookmarks to FluidDB, but it

could obviously do so, and I imagine I’ll add that capability some

time over the next few weeks when I decide what I think the best way

to do it is. I think this approach mirrors del.icio.us most directly

and naturally and is a good choice if you want to use FluidDB

primarily for social bookmarking, perhaps expanding to take in tags

with values. It requires you to install two python packages, both

available on github. You can find information in this blog entry.

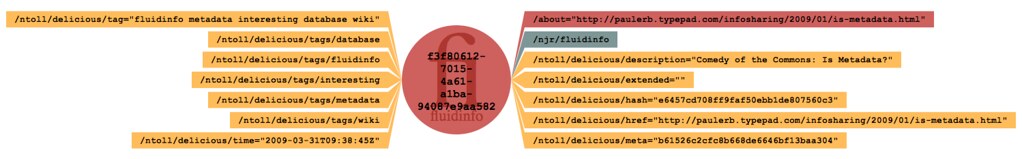

But there's a simpler and better alternative from

Nicholas Tollervery (@ntoll), who works at Fluidinfo.

He has written a single script that just prompts you a few

questions before it does the upload. It also uploads

all the information, rather than just the tags, as mine does.

I imagine we’ll simplify both approaches over the coming weeks.

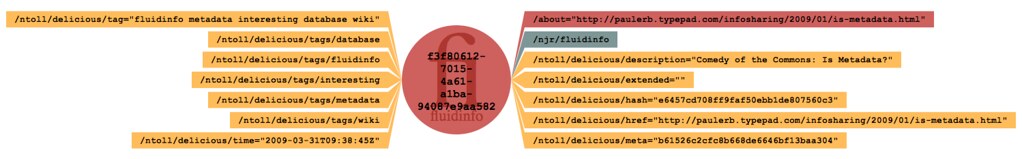

This diagram shows the object for a webpage Nicholas and I have both

bookmarked

I found this bookmark my using the FluidDB query

has njr/fluidinfo and has ntoll/delicious/tags/fluidinfo

I had a single del.icio.us tag for this, whereas Nicholas had several.

Nicholas has chosen to prefix all his delicious tag names with delicious/tags,

which is why the are so long, but by default both his and my script

put all the main data in the top level, so that a del.icio.us tag

njr/fluidinfo

becomes a FluidDB tag

njr/fluidinfo,

and the title and notes attributes are stored using FluidDB tags

title and

>notes respectively.

Like my script, Nicholas's currently doesn't tag anything in the case

of private bookmarks, but his script does create all FluidDB tags

that you use, even if some of them are only used for private bookmarks.

So if the existence of a particular tag you have is secret, that would be

a reason not to use his script.

Nicholas's code is available from github and also (perhaps more easily) from the python package

index PyPI,

at this location.

This allows you to install it with setup tools or easy_install etc.

I imagine he'll blog about it soon.

An “old del.icio.us” alternative

As will be clear by now, del.icio.us has been pretty influential in my

life. A few weeks ago I had an idea for a web site not initially very

similar to del.icio.us, which I have been developing slowly.

I don’t want to

go into details now, but it’s in the general area of checklists,

allowing users to find, create, share and use checklists of various

kinds. It’s a social application on exactly the del.icio.us model (by

which I mean, it has no explicit ratings and is useful even if no one

else uses it). More generally, you can think of it as a kind of

del.icio.us for user-created and re-mixed content, specifically around

checklists for now.

A week ago today I realised that since I was effectively building

almost everything you need for del.icio.us, I could easily extend my

new website to include an actual del.icio.us alternative, i.e. I could

allow users to save bookmarks for websites as well as for content they

create in the application itself. I’m generally nervous about

extending small ideas and making them more complex, but this seemed

like a very minor extension, and I have become increasingly nervous about

the future of del.icio.us ever since Yahoo acquired it. News of

Yahoo’s intention to divest itself of del.icio.us

prompted me to stop wondering and start implementing on

Thursday night. I hope to make a limited service available in the

next few days. (I’ll update this post and create a new one announcing

it when I do.)

Its functionality will be limited at first, but will include (does

include, in fact) the ability to import all bookmarks and tags from

del.icio.us (private and public) and maintain their state, and all the

most basic functionality (creating, editing, deleting bookmarks).

There will also be limited social functionality (looking at tags

across users etc.) and, of course, the ability to export your data in

the same XML format as the one del.icio.us uses.

Over time, I’ll try to make it ever more like the pre-Yahoo del.icio.us,

as far as I can remember that.

And I think it’s very likely that I will

also offer users the option of duplicating bookmarks in FluidDB, to

allow for richer sharing, and to provide exactly the del.icio.us-like

FluidDB client that I would love myself.

Of course, I realise there are a dozen or more del.icio.us

alternatives already up and running, and they are clearly a more

stable, safer bet. But I hope that at least a few people will

think this approach is interesting enough to try.

I will probably add an option to hide all the non-bookmarking functionality,

from my site, though I don’t think it will really distract much anyway.

(I’ll probably turn it all off until it’s ready, next year, for now anyway.)

Carol Bartz may not be bringing much Christmas cheer at Yahoo, or to

del.icio.us users, but I hope that my embryonic del.icio.us

replacement and FluidDB can be part of an ecosystem of alternatives

that will end up being more empowering for users and will allow

hard-core del.icio.us fans to have a future more like the del.icio.us

of old.

Maybe, it will be glor.io.us.